Grief in victory: Therapeutic writing helped to heal a nation after the First World War

My latest piece, originally published a few week ago in The Conversation. Your comments are welcome!

–

Most people have seen images of Allied victory celebrations marking the end of the First World War, but was everyone in a celebratory mood? For many, grief overwhelmed relief. Grief was arguably the defining experience of the entire conflict. However, the psychology of that grieving has been relatively overlooked.

The British, in particular, are famous for needing to show a stiff upper lip when facing loss. But what lies behind that facade? Cultural icons of the day, including Arthur Conan Doyle, Rudyard Kipling and J.M. Barrie, as well as the emerging writer Virginia Woolf reveal insights into the experience of grief at the moment of victory.

Like an approximate three million British people, these writers had also lost loved ones during the war, but their grieving was shaped by prewar traumatic losses. Unlike most, they had the capacity to renegotiate loss through creative writing that could be therapeutic. As wounded healers, they shaped and gave voice to the culture?s collective trauma.

Prayer not celebration

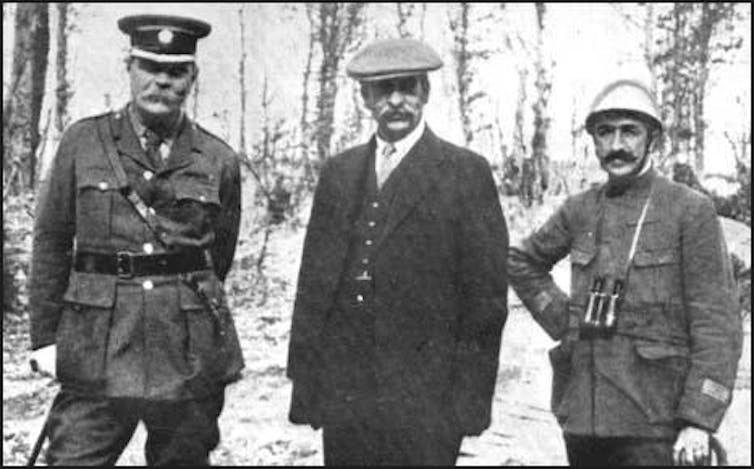

These writers articulated bereavement on Armistice Day regardless of their initial stance towards the war. Arthur Conan Doyle initially treated the war as an adventure, publicly proposing inventions such as life belts for sailors. Rejected for service because of his age, he wangled his way to the ?wonderful? front wearing a fake uniform ostensibly to collect information for his six volume study of the war.

By Armistice Day his attitude had changed dramatically. At 11 o’clock he saw a flag-waving woman waltz into his staid hotel. He rushed to Buckingham Palace where he witnessed singing, cheering and a man downing a bottle of whisky raw. This angered him since, ?It was the moment for prayer.? Doyle?s eldest son Kingsley had died two weeks earlier from influenza, weakened from war service.

Shocked and stupefied

Rudyard Kipling penned propaganda and actively recruited soldiers for the war, including his son John, pulling strings to get him enlisted even though the boy?s poor eyesight made him unfit for service. He was killed just weeks after reaching the front in 1915, his body never recovered despite his father?s obsessive efforts to find the grave. This story is told in a compelling film My Boy Jack.

On Armistice Day, Kipling?s reaction, expressed in a letter to a fellow bereaved father was intense, ambivalent and dark. He captured his shock graphically: ?Here we are in England ? dazed and stupefied with the guts of Central Europe trailing round our legs ? the whole shoot collapsed like the last scene of some Wagnerian opera.?

He was angry that the ?Hun? was not pursued further, back into Germany. Finally, his grief surfaced: ?We feel the loss of our young ?uns more bitterly now in peace, even than we did in the heat of the war of the early years.? He closed the letter by revealing that he had escaped the peace celebrations and ?bolted home from town and had my dark hour alone.?

Lost boys

J.M. Barrie had also supported the war effort, but anxiety regarding his surrogate sons (and the models for Peter Pan and the lost boys) the Llewelyn-Davies boys, two of whom joined up, shifted his attitude. When George Llewelyn Davies was killed in 1915 Barrie was devastated.

In Paris on the 11th of November, J. M. Barrie found most memorable ?the happy faces,? but they revealed to him, ?it is finished? rather than ?we have won.?

A pacifist mourns

Virginia Woolf was a pacifist, and so one would expect that she would be elated at the end of the war. However, she also lost loved ones during the conflict. Her childhood friend and fellow writer, Rupert Brooke, died in Greece; in 1915, two of her cousins died. Her brother-in-law, Philip Woolf, was severely wounded and the other, Cecil Woolf, killed, both in 1917.

On Armistice Day, Virginia Woolf wrote to her sister, the painter Vanessa Bell, and told her she felt ?immensely melancholy.? She said rejoicing ?has been very sordid and depressing.? She lamented the ?very sentimental or completely stolid reaction of the London poor,? and then added, ?but I suppose the poor wretches haven?t much notion how to express their feelings.?

She implies that she has the advantage of being able to articulate her feelings of grief in words, while others cannot and so they fall back on blunted, mindless celebrations.

Wounded healers

Many writers possess this gift of seeing and expressing what others cannot. But in many cases, this has been gained at great cost. In Mourning and Mysticism in First World War Literature, I detail the severe trauma that all of these writers suffered in earlier years, from Kipling being abandoned in England by his parents from age six to 12, not knowing when or if they would return from India, to Virginia Woolf suffering sexual abuse and the loss of her mother at age 13.

I believe the writers developed an insecure-avoidant attachment pattern that persisted into adulthood. This means that they tended to suppress feelings and rely on cognition in relationships. According to attachment theorist Patricia Crittenden, approximately one-third of children manifest this pattern. In wartime, avoidant types cope by suppressing emotion, hence the stiff upper lip.

These writers demonstrate the more complicated pattern of being avoidant-resistant, meaning that in addition to dealing with feelings on a cognitive level, they tend to be preoccupied with past relationships. They think about feelings and attend to emotional cues carefully, skills actually advantageous to writers. They discover that losses can be renegotiated through imaginative play in the ordered and safe form of fiction.

Recalling the dead

Early loss for these writers sensitized them to loss during wartime and made them receptive to mysticism, whether through spiritualism or some other means of imaginative connection with the dead.

Most famously, Doyle contacted family members through seances including his son, and helped others to do so. He wrote extensively about spiritualism, travelling the world as the St. Paul of spiritualism, and provided comfort for thousands, though this work has been disparaged by critics.

A week after his beloved George died, Barrie had his play, The New Word produced. It connects a father?s anxiety about his soldier son?s departure for the front with the loss of the boy?s brother as a child. Two other popular plays (both recently revived), Dear Brutus and A Well Remembered Voice, deal respectively with lost chances and a father?s enhanced relationship with the spirit of his soldier son.

After the war, Kipling wrote poems about grief far removed from earlier jingoism, and arguably his best short stories, masterpieces of compressed emotion. Several stories speculate about spiritual connections between soldiers and loved ones, such as ?A Madonna of the Trenches? and ?The Gardener.?

In her first modernist novel Jacob?s Room (1922), Woolf wrote a memorial to her brother Thoby, who died in 1906, overlaid by her testament to an unknown, universal soldier she named Jacob Flanders. In 1925 she explored the uncanny connection between a shell-shocked soldier and a society hostess in Mrs. Dalloway.

While writing proved only temporarily therapeutic to these writers, and war losses permanently altered their lives, they left a richly creative legacy that has outlived their grief and helped to heal a generation.